Self-proclaimed “not a professional historian” Peter Timms begins his 2009 book, In Search of Hobart with the most captivating line:

‘Too far south for spices,” Abel Tasman wrote dismissively in 1642 on sighting the island now bearing his name, “and too close to the rim of the earth to be inhabited by anything but freaks and monsters.” Wrong on both counts, as it happened, he sailed on rather grandly into the Pacific looking for somewhere more worth discovering. No other European bothered to put in an appearance for almost a century and a half.

“Too far south for spices, and too close to the rim of the earth to be inhabited by anything but freaks and monsters” is a powerful line.

So while in Amsterdam I went searching for the journal so I could read the line in context because in all my research I couldn’t find it online.

Translation of the Journal of Abel Tasman, 23 November 1642 to 5 December 1642

Bold emphasis mine. Journal’s ISBN is 9040082057.

23 November

Good weather and the wind southwest with a continuous breeze. In the morning we noticed that our rudder was broken above in the hole of the rudder post. We held close to the wind with small sail and fastened a beam on both sides.

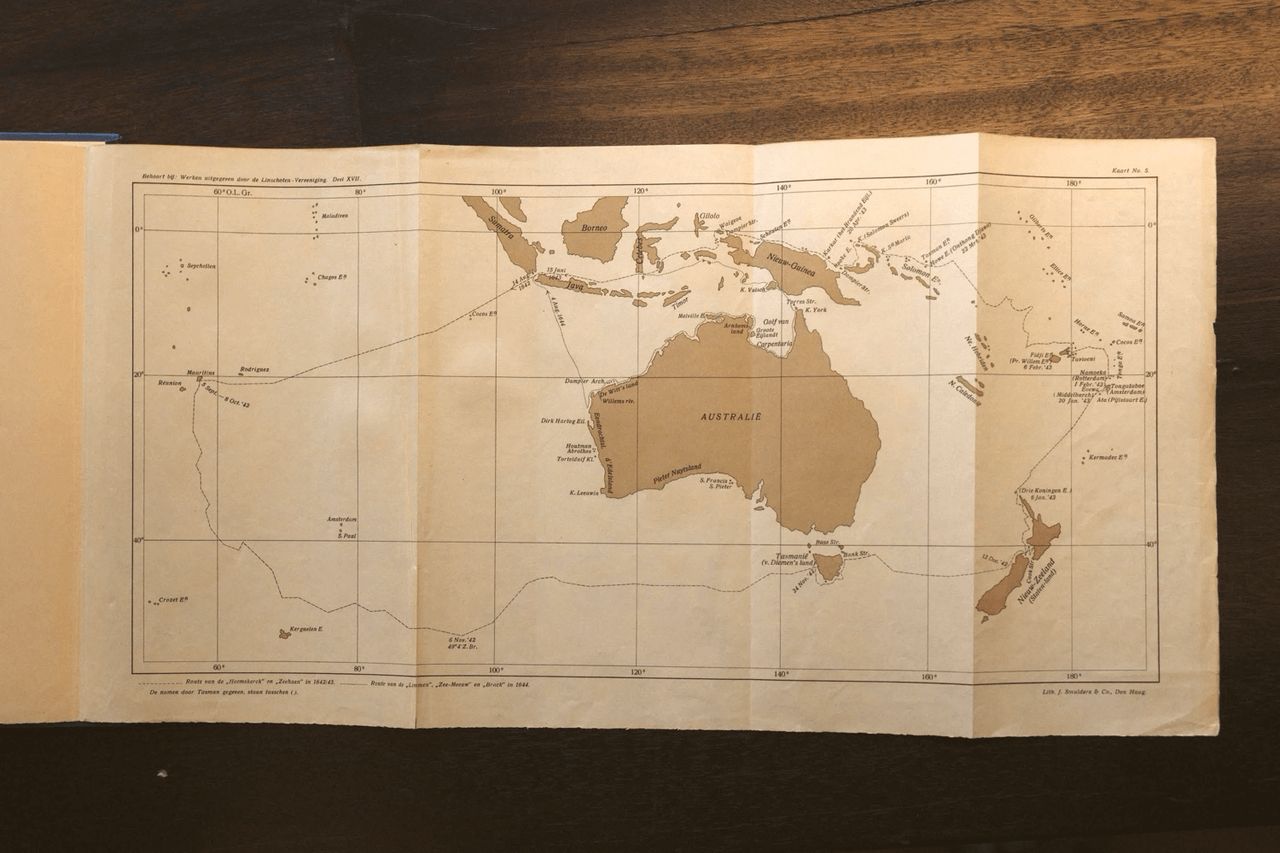

At midday we found the altitude of 42 degrees 50 minutes and longitude 160 degrees 51 minutes, course maintained east and sailed 25 miles. We had here one degree northwesterly variation which decreases very rapidly here. By our estimation we now have the western side of New Guinea to the north of us.

24 November

Good weather and clear skies. At midday we found the latitude of 42 degrees 25 minutes and longitude 163 degrees 31 minutes, course maintained east by north and sailed 30 miles. The wind from the southwest and then south with a light topsail breeze. After midday, around four o’clock, we saw land. We had it east by north of us, estimated at ten miles. It was very high land. Towards evening we saw in the east-southeast three more high mountains and in the northeast we also saw two mountains. That is less high than the land to the south. We had here a true compass. In the evening in the first glass after the watch was set, we put before the ship’s council and the petty officers whether it would not be better to put out to sea from the shore, and asked if they considered that advisable. It was jointly decided to lay off from the shore after three glasses and go in that direction for ten glasses, then sail again towards the land, as appears more fully from today’s resolution. Thus we sailed at night after three glasses with southeasterly wind away from the shore and had bottom at 100 fathoms: clean, white fine sand with small shells. Afterwards we sounded again, and found black coarse sand with pebbles. At night we had a southeasterly wind with light breeze.

25 November

In the morning calm, we let the white flag and the topgallant pennant fly from the stern, whereupon the ship’s officers of the Zeehaen with their helmsmen came aboard us. We convened the broad council and thereby decided what can be seen in today’s resolution, and is there extensively explained, to which we refer here. Towards midday we got the wind southeast and then south-southeast and south; then turned towards the shore.

In the evening around five o’clock we came under the shore. Three miles off the shore we had coral bottom at 60 fathoms, one mile off the shore we had clean, fine white sand. This coast appeared to lie southeast and northwest, a smooth coast. We had the altitude of 42 degrees 30 minutes and as average longitude 163 degrees 50 minutes. We sailed away from the shore again, the wind ran south-southeast with topsail breeze.

When one comes from the west and has four degrees northwesterly variation, then one must look out well for land, because the variation decreases very rapidly here. Should it happen that one got a hard storm from the west, then one would have to heave to and not sail further. Here by the shore one has a true compass. We took the mean longitude, which we determined and averaged together, from which we find that this land lies at longitude 163 degrees 50 minutes.

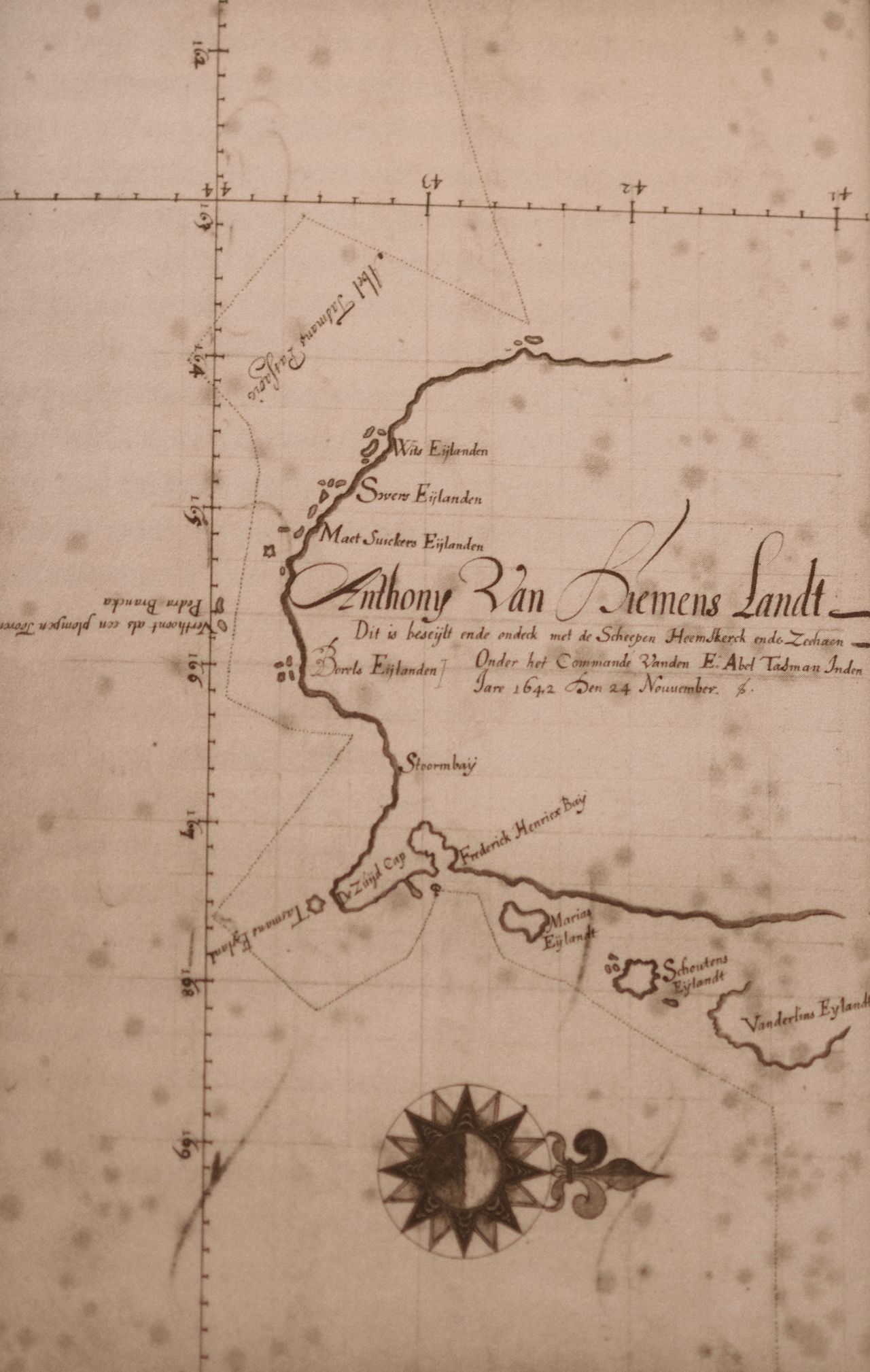

This land is the first land that we found in the South Sea, and it is unknown to any European people. Therefore we have given this land the name of Anthony van Diemen’s Land, in honour of the noble lord governor-general, our high authority who sent us out to make this discovery. The islands around it, as far as we could see them, we named after the noble gentlemen councillors of the Indies, as can be seen on the chart that was made of it.

26 November

We had the wind easterly with light breeze and foggy weather, so that we could see no land. We estimated to be about nine and a half miles off the shore.

Towards midday we let the topgallant pennant fly, whereupon the Zeehaen immediately sailed towards us, and we called to them that Mr Gilsemans should come aboard us, whereupon Gilsemans without delay betook himself to our ship. We told him what is reported in the note below, which he took to their ship to show to skipper Gerrit Jansz and give their helmsmen this order:

The officers of the fluyt ship Zeehaen shall describe in their daily registers this land, which we saw yesterday, at longitude 163 degrees 50 minutes, as our average bearing was, and take this longitude as a fixed point and from here recalculate the longitude anew. Whoever previously had the longitude of 160 degrees or more shall now make his calculation from this land; this is done to prevent all errors as much as possible. The command of the Zeehaen shall give the same order to the helmsmen and also comply with it, because we have found it so. The charts that are made of this land shall situate the land at the longitude mentioned above of 163 degrees 50 minutes.

Done on the ship Heemskerck, date as above, signed Abel Jansz Tasman.

At midday we estimated to be at south latitude 43 degrees 36 minutes and longitude 163 degrees 2 minutes, course maintained south-southwest and sailed eighteen miles. We had half a degree northwesterly variation. In the evening we got the wind northeast and set our course east-southeast.

27 November

In the morning we saw the coast again, our course was still east-southeast.

At midday we estimated to be at south latitude 44 degrees 4 minutes and longitude 164 degrees 2 minutes, course maintained southeast by east and sailed thirteen miles. It was thick, misty, foggy, rainy weather, the wind northeast and north-northeast with light breeze. At night after seven glasses in the first watch we lay the ship to with small sail. We dared not sail further because it was so dark.

28 November

In the morning still dark, misty, rainy weather. We made sail again and set our course due east and then northeast by north. Saw land northeast and north-northeast of us and sailed straight towards it. The coast lies here southeast by east and northwest by west. This coast bends here as far as I can see towards the east. At midday we had by estimation the altitude of 44 degrees 12 minutes and longitude 165 degrees 2 minutes. Course maintained east by south and sailed eleven miles. The wind came from the northwest with a light breeze. In the evening we came under the shore. Here lie under the shore some small islands of which one shows itself like a lion, which lies about three miles from the mainland. In the evening we got the wind east and hove to at night with small sail.

29 November

In the morning we were still by the cliff that shows itself like the head of a lion. We had the wind westerly with topsail breeze. We sailed along the shore which here lies east and west. Towards midday we passed two cliffs of which the westernmost shows itself like Pedra Branca by the coast of China.

The easternmost shows itself like a high blunt tower and lies about four miles from the great land. We sailed between the cliffs and the land.

At midday we estimated to be at altitude 43 degrees 53 minutes, longitude 166 degrees 3 minutes, course maintained east-northeast and sailed twelve miles. We sailed along the coast. In the evening around 5 o’clock we came before a bay. It looked as if we would find a good roadstead there.

We decided with the ship’s council to run in there, as appears from the resolution. When we were almost in the bay such a hard wind arose that we were forced to take in our sails and run to sea again with small sail, because it was impossible to anchor with such wind. In the evening we decided to put out to sea at night with small sail so as not to be driven ashore with that storm. This is all to be read more fully in the above-mentioned resolution, to which we refer here to avoid unnecessary elaborations.

30 November

In the morning at daybreak we turned the ship towards the shore. We had been driven so far from the shore by wind and current that we could barely see the land. We did our best to get closer to it again. At midday we found the altitude of 43 degrees 41 minutes, longitude 168 degrees 3 minutes, course maintained east by north and sailed twenty miles with storm and tempestuous weather. Here the compass points true. Shortly after midday we turned it about to the west with hard, unstable wind, and then turned it about to the north with small sail.

1 December

In the morning the weather was somewhat better. We set our topsails, the wind west-southwest with topsail breeze. We set course towards the shore. At midday we had the observed altitude of 43 degrees 10 minutes and longitude 167 degrees 55 minutes, course maintained north-northwest and sailed eight miles. It became calm. We let the white flag fly at midday whereupon the friends from the Zeehaen came aboard. We decided jointly to make for the land (as soon as wind and weather would permit it) the sooner the better, both to take note of the particulars of the land, and to see if any refreshment could be obtained, as today’s resolution shows more fully. Afterwards we got a little wind from the east and ran towards the shore to see if we could find a good roadstead here. About an hour after sunset we dropped anchor in a good harbour at 22 fathoms white and grey fine sand, with gradually rising ground, for which we are grateful to almighty God.

2 December

Early in the morning we sent pilot-major Frans Jacobsz with our boat with four musketeers and six rowers, each with a pike and cutlass at their side, together with the small boat of the Zeehaen and one of their petty officers and six musketeers to a cove that lay northwest barely a good mile from us, to see what useful things (fresh water, food, timber or otherwise) could be found there. Three hours before evening they returned, with various samples of vegetables (which they had seen growing abundantly), some not unlike a vegetable that grows at the Cape of Good Hope and is suitable for use as greens. Another vegetable was long and salty, and seems somewhat like sea parsley. The pilot-major and the petty officer of the Zeehaen reported the following:

That they had rowed well over a mile around the mentioned point, where they found high, flat land with vegetables (not planted but brought forth by God and nature), timber in abundance and a flowing water place and many empty valleys. That water is indeed good but rather difficult to get, and the stream runs so slowly that it can only be scooped with a bucket.

That they heard the sound of people, also music - almost like a trumpet or a small gong - which was not far away, but they had seen no one.

That they had seen two trees of about two to two and a half fathoms thick and 60 to 65 feet high under the branches, of which the trunk was worked with flint stones to be able to climb in them and empty bird nests. In the trunk were steps cut five feet apart, so they assume that there are very tall people here or that the inhabitants know how to climb those trees in some way. In one tree the carved stairway seemed so fresh and green, as if it had been carved out no four days ago.

That the tracks they had seen somewhat resemble those of tiger claws. They also brought aboard some droppings of, it seemed, four-footed animals, and also some (at first sight) beautiful gum that drips from trees and has something of shellac about it.

That around the east point of this bay at high water a depth of thirteen to fourteen feet was found. At ebb tide the water falls there about three feet.

That they had seen ahead around the same point a multitude of gulls, wild ducks and geese, but not inland, although they did hear bird sounds. They found no fish, except for some mussels, which stick together in clusters in some places.

That the land is mostly covered with trees, which stand so far apart that one can walk everywhere and see far ahead, so that when landing one can always get sight of people or wild animals. The view is not obstructed by dense vegetation or undergrowth, which gives a good opportunity for reconnaissance when landing.

That they had seen in various places many trees that were burned above the foot to deep inside, with here and there a bottom of earth as a fireplace. The trees were burned as hard as stone by the fire-making.

Shortly before we got our vessels in sight, we saw thick smoke rising from time to time on land (which lay west by north of us). We therefore assumed that our people were making that as a signal, because they waited so long to return. We had indeed ordered them to return with haste, on the one hand to quickly learn their findings, on the other hand to be able to go examine another place if they found nothing useful, so that no time was lost uselessly. When our people came back aboard, we asked if they had been in that direction and made fire, to which they answered no, but that they had also seen smoke at various times and places in the forest. There must therefore without doubt be people here, who are probably of extraordinary height. We had today many variable winds from the east, but the greater part of the day there was a stiff continuous breeze from the southeast.

3 December

We went with merchant Gilsemans and our vessels as yesterday with musketeers and rowers with pikes and cutlasses to the southeast side of this bay, where we found water, but where the land was so low that the fresh water was broken by the surf of the sea and became salt. To dig wells this land was too rocky. Therefore we returned aboard again and called together the council of our two ships, with which we decided and approved, as today’s resolution shows, to which we refer, to be able to stay brief here. After midday we went with the vessels, with pilot-major Frans Jacobsz, skipper Gerrit Jansz, merchant Isaac Gilsemans of the Zeehaen, junior merchant Abraham Coomans and our head carpenter Pieter Jacobsz to the southeast side of this bay.

We had with us a post with the company’s mark carved in it, and the Prince’s flag. We wanted to erect that post there so that it would be clear to later visitors that we had been here and had taken the land as possession and property. When we were halfway there, it began to blow hard and the sea began to run so hollow that the small boat of the Zeehaen, in which the pilot-major and Mr Gilsemans sat, had to return to the ship again. We continued with our boat. Close under the shore in a small bay, which extended southwest from the ships, the surf was so strong that we could not approach the land without danger of smashing the vessel. We let the mentioned carpenter alone with the post and the Prince’s flag swim to land and remained lying on the wind with the boat. We had him erect the post with the flag on top approximately in the middle of the bay, by four high, easily recognisable trees that stand there in a half moon.

The post stands before the foremost tree. This tree is burned just above the foot and it is the highest of the four, but it seems lower because it stands in a hollow. It has at the top above its crown two high protruding dead branches that are set with small dead side branches and knots, so that it looks like the antlers of a stag. Next to it is a very green and round branch with leaves, whose side branches by their equal dimensions adorn the trunk and resemble the top of a larding needle. After the head carpenter had performed the aforesaid in sight of me, Abel Jansz Tasman, skipper Gerrit Jansz and junior merchant Abraham Coomans, we rowed the boat as close to the shore as we dared and the mentioned carpenter swam through the surf back to the boat and afterwards we rowed back aboard.

We leave our successors and the inhabitants of this land - who did not show themselves, although we suspect they watched our doings closely - the mentioned post as a sign that we have been here. We did not search for vegetables because we could only reach the land by swimming, so it was impossible to get anything into the boat. This whole day the wind was mostly north. In the evening we took a bearing on the sun and found three degrees northeasterly variation. With the setting of the sun we got a hard north wind which rose hand over hand from the north-northwest to such a hard storm that we were forced to strike both yards and drop our stream anchor.

4 December

With the break of day the storm abated. The weather was better and with the wind off the shore from west by north we had the stream anchor wound up again. When the anchor was wound up and above water, we saw that both arms were broken off so far that we got nothing but the shank above. We also weighed the other anchor and then got under sail, to sail north inside along the northernmost islands and seek a better watering place. We lay at anchor here at south latitude 43 degrees and 176½ degrees longitude. Before midday the wind was westerly. At midday we had the observed altitude of 42 degrees 40 minutes, longitude 168 degrees, course maintained northeast and sailed eight miles. After midday the wind was northwest. We had this whole day very variable winds: in the evening west-northwest with hard wind, and west by north and west-northwest. We turned it to the north and saw in the evening a round mountain north-northwest of us at about eight miles distance.

Our course sharp to the wind northward. During the sailing out of this bay and also throughout the day we saw much smoke from fires rising along the coast. The trend of the coast and the adjacent islands we should describe here, but to be brief we leave it and refer to the chart that was made of it and is attached herewith.

5 December

In the morning the wind northwest by west, we held the same course. The high round mountain that we saw the previous day lay due west of us at six miles, from where the land bends away to the northwest, so that we can no longer sail along the coast here. Because the wind was almost contrary, we had the ship’s council and the petty officers come together. We proposed - and so it was decided and afterwards called out to the authorities of the Zeehaen - to set the course due east according to the resolution of 11 November, and to sail on that course to the full longitude of 195 degrees or the Solomon Islands. This is all to be seen more fully in the resolution of that date. At midday we had the estimated latitude of 41 degrees 34 minutes, longitude 169 degrees, course maintained northeast by north and sailed 20 miles. We set our course due east, to make further discoveries, and also not to fall into the variable winds between the trade wind and the counter-trade wind. The wind northwest with continuous breeze. At night the wind west with stiff continuous breeze and good clear weather.